(Posted by Marina)

Ordinarily, I don’t watch television. At all. But the week that Katrina hit, my partner was out of town and unreachable by phone, and I started watching hurricane coverage. I couldn’t believe what I was seeing---the human suffering and how as the days passed, not much seemed to be changing. I wasn’t sleeping well, and I was feeling helpless, angry, and upset. Then I went on the Internet, and began realizing how many animals were in trouble. What really touched me most deeply was the story of Snowball. You probably heard about this, or saw the clip on the news: A young boy was carrying his little white dog onto a bus, to be evacuated, and he was told by someone in a uniform that he had to leave the dog behind. He put him down and then started screaming, “Snowball! Snowball!” over and over, and crying and sobbing until he vomited.

In her book, "Animal Grace: Entering a Spiritual Relationship With Our Fellows Creatures," Mary Lou Randour says: “Animal suffering usually goes unrecognized and is tacitly supported by normative culture, the government, and other public and private institutions.” Seeing what had happened to Snowball was a reminder of that reality, a very painful one, because it was so unnecessary that this child be separated from his dog, but the path to spiritual wholeness often begins with the invitation to become aware of suffering.” I felt I had no refuge from these feelings, but then I realized that this was really an invitation, a gift, in disguise, and I knew I needed to take action. There is a verse in the Buddhist text, "Anguttara Nikaya":

"My action is my possession,

my action is my inheritance,

my action is the womb which bears me,

my action is my refuge."

So last October, I went down south, to Mississippi, to work with other volunteers at an emergency animal rescue center, helping animals displaced by Hurricane Katrina. This wasn’t something I decided to do so much as I took refuge in it. My action literally became my refuge. I had signed up to help with animal rescue with three or four groups, went online a lot, sent money. I was starting to think that this was all I COULD do. Then, on September 26th, Best Friends Animal Society called and asked me to come down to southern Mississippi, to the St. Francis Animal Sanctuary. St Francis is located near Tylertown, Mississippi, which is a very beautiful, very poor and very rural area 100 miles north of New Orleans. I left home on October 1st. It took me 27 hours to get there, by bus to Chicago, then by train to Jackson, Mississippi, and then I rented a car and drove 100 miles further south .

Before I get too deeply into what it was like there, a bit about Best Friends Animal Society: They’re based in Kanab, Utah, and they are the largest animal sanctuary in the country, very focused on creating positive alternatives; they put out a quarterly magazine with the subtitle, “All the good news about animals, wildlife and the earth.” To see lots of photos of all the good work they do, watch videos (some heartbreaking, some sweet, some funny), join and donate, go to http://www.bestfriends.org . You can also buy their book, Not Left Behind, a photo book about the rescue. From September 5th, 20005 until May 10th, 2006, their hurricane animal rescue headquarters was set up at St. Francis Animal Sanctuary, a modest-sized animal shelter founded by Francis & Sylva Battista about six years ago; he’s head of the Outreach program in Kanab. Best Friends worked with the Humane Society and many other groups to locate and rescue animals abandoned, lost, and injured, in New Orleans and all of the areas affected by Katrina and Wilma. When I was there last fall, Best Friends and other groups would send trucks into New Orleans every day, and then bring animals back to Tylertown, to the St. Francis Sanctuary, with its buildings, staff and infrastructure already in place, so it was a good place to base this kind of operation. We had half a dozen volunteer vets and vet techs, and Best Friends staffers, as well as volunteers, to care for the animals. St. Francis was built on the grounds of an old dairy farm. It has three buildings: one a medical clinic, another was the main cat building, with a small office, and the third has a kitchen, room for stores, some screened rooms for cats, and living quarters upstairs for the sanctuary staff. And each of these buildings had a laundry---we used a lot of water, and they actually had to have their well drilled deeper while I was there, as they were running out.

There was at that time a 30-day quarantine before the animals could leave the state. Trucks left Tylertown every day---except on those days when the government was preventing them from going in---to go to New Orleans and bring back as many animals back as they could fit. They often had to leave animals behind because there wasn’t enough room for them all. Animal rescue groups (all no-kill shelters) from all over the country as well as Canada drove to Tylertown and would take back as many animals as they could, and then, if the animals weren’t reunited with their people, the groups would foster them until permanent homes could be found. Best Friends took animals back to Utah, too, of course.

To give you a rough idea of the numbers involved, and what it was like when I was there, as of October 25th, they had had more than 2,000 animals come through the rescue center. In November, they had about 450 animals on any given day. Reunions that had occurred at the center at that point numbered 112, plus more from foster homes and groups around the country. By the time they closed down in May, it was up to 3,300, and over a thousand people had come through as volunteers. Most of the rescued animals were dogs and cats, but I also saw about a dozen rabbits, a small flock of chickens, a few ducks, a 400-pound pot-bellied pig, two iguanas, some tanks of fish, some tarantulas, and a corn snake, who was given her freedom, of course, in an appropriate and undisclosed area. (Pet stores abandoned animals, in some cases, but we did hear of one where the staff came back as soon as they could and took them all home.) Horses were being taken someplace else, and I was told by one of the vets that the reason we had no birds or “pocket pets,” (i.e., gerbils, mice, rats, hamsters) was because those animals can only go two days or so without food and water.

As I said, Tylertown is just two hours north of New Orleans, so it was an excellent place to base animal rescue efforts, but it felt almost dangerously close to me, I really didn’t know what I might be getting into. I was excited to be going, but afraid to go, and I almost turned back at Amtrak in Chicago. I was afraid of camping out, bringing all our own food & water, being completely self-sufficient, fearing the heat, dirt, running out of food, fire ants, my health, wanting to take all the animals home. Most of all, I was afraid because of an image that kept running through head from the movie, “Gone With the Wind,” of Scarlett O’Hara on the battlefield, where she’s kneeling by a wounded soldier’s cot, and then the camera moves further and further away, up into the sky, until she’s only a tiny dark speck in a sea of white beds and bandages, overwhelmed, and overwhelming by sheer numbers. I think that’s why most people are afraid to do this kind of work: fear of being overwhelmed by suffering. But it wasn’t like that at all. It was more like being at a huge animal shelter, with lots of activity, people running around with cell phones (our only phones), looking for laundry detergent or lugging dirty kennels over to the power washer, lots of dogs barking, and so on.

And there are other reasons why it wasn’t overwhelming, and why I felt empowered, not helpless. I could always make choices about how I wanted to spend my time: so when I needed to rest, I did. There was a screened-in room in the main cat building where, once cats had been there for a few days and met certain health criteria, as many cats as could comfortably fit left their carriers to spend all their time. When I was there, it just so happened that all the cats were young, black cats---they were all from the same house---and if you went in and lay down in the middle of the room, they would come and climb all over you. When someone started feeling, they’d say, “I’m going to go do some Black Cat Meditation," or "Black Cat Therapy.”

And I also chose not to unload the trucks when they returned from New Orleans every night (anytime after 10 pm up until 2 am), and that was one way I witnessed suffering so as to raise my awareness, but not to brutalize my psyche by exposing myself to more than I felt I could handle. I knew that there were animals who made it through the ride from New Orleans, but died shortly after arrival, and others were in such bad shape that they went straight to the Medical Clinic, so I never saw them. (Only the vets and vet techs were allowed to enter that building.) These were animals who had been swimming in toxic water and sewage, who had chemical burns all over their bodies and internally, as well, from drinking the water, who had been eating rodents or garbage, and who were often traumatized, terrified to the point where it could be hard to tell a feral cat from one who had been someone’s companion.

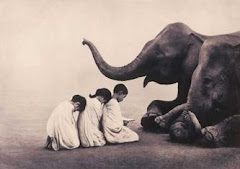

But what the animals needed as much as they needed to be taken out of peril was simply to feel loved and attention paid to them. That’s easy, of course, but because there were so many of them, I felt overwhelmed at times. My primary spiritual practice is that of Thich Nhat Hanh’s Order of Interbeing, socially engaged Buddhism; I had an awareness of how ahimsa, which is harmlessness to all living beings and the bedrock principle for all religions, is a process, not just a goal. You may have heard the story of the boy who was walking down the beach, littered with hundreds of starfish who had washed up on the sand and were dying, and of how he was tossing starfish back in, one after another. His father said to him, “What’s the point of doing that? You’ll never be able to save all those starfish. It doesn’t matter.” And the boy replied, gently lofting a starfish into the water, “It mattered to that one.” I tried to keep that story in mind, especially when I was tempted to make the cats wait for attention until I’d cleaned their boxes and fed them---you can’t do that, I quickly learned. You must love them as you go. When I was actually there doing the work, I had a strong sense of how I couldn’t help them all at once, just one at a time, but it was enough---that in itself was making a difference.

I spent four nights at St. Francis, camping out in a tent near the front gate, which was locked every night at ten. Right away, I told the staff that that I know cats better than dogs---although I love dogs, too, I’ve not lived with any since I was very small---and was told that they needed new cat workers since two were leaving the next day. So I was now an official cat building volunteer. The days went like this: No matter how late we had gone to bed, we all got up with the dogs, who started barking at about 5, we dressed, ate (many of us stood to eat out of the trunks of our cars, although some had brought luxuries like campstoves and chairs), maybe washed a little, and then went up to the cat building, not to return until after lunch (which Best Friends fed us---great vegetarian meals, I might add). I fed and cuddled cats, cleaned cages & litter boxes, changed water, and I did loads and loads of laundry: Literally 24 hours a day, the washer and dryers were running---we went through that many towels and blankets). I also made phone calls, and input info into the database of lost animals. At its peak, I believe there were around 10,000 hurricane animals on PetFinders.com.. When the trucks came back from New Orleans, usually very late, as I said, I helped with intake: each animal got a Best Friends number, had its picture taken, got vaccinated and microchipped, and we filled out paperwork to track every detail that might help reunite the animals with their people.

That was, and still is, a primary goal of Best Friends in this effort: to reunite these animals with their people. The first day, two men, tired and dirty, came looking for their three dachshunds. We had only one of them, but they were overjoyed. They cried. While I was at St. Francis, I made some phone calls to a woman who was staying in a hotel in Baton Rouge; she and her husband had been forced to evacuate without their two cats, Fifi and Cici, but they had sent a letter to Best Friends, describing their whereabouts, in hopes that they would be rescued. I looked through a few hundred photos, and there were several anxious phone calls (with the cell phones forever cutting out!) to try to figure out if we had rescued their cats. As it turns out, Tasha and Daryl not only found Fifi and Cici through Best Friends, but they were reunited with them on Tasha’s birthday. She was so happy, she said, “You don’t know what this means to me. It’s like you’ve given me my life back.”

Everyone worked together, regardless of religion or political differences. There is such political polarization in this country right now that I was almost wondering if such a thing was possible---to cross the red & blue lines and work together on something. But we did. You didn’t know people’s last names. Usually we just told each other where we’d come from, and maybe what we did for a living. It was a challenge in many ways. Personality differences constantly threatened to make us forget why we were there; this is true at any job, I suppose, but how we resolved these differences was unique---the animals were part of that. We disagreed on how best to care for the animals at even the tiniest level (e.g., should the cats be fed treats, and if so, what kinds, etc., etc.) People got very territorial about how best to do the laundry, whether or not we should rearrange the supply shelves, etc.. And sometimes in the cat building, we got too loud, and the cats would become distressed; they’re very sensitive to raised voices and angry gestures---and then we would all calm down, knowing the effect we were having on them. This is another way the animals taught us spiritually---not harboring anger is a component of ahimsa.

There were also disagreements about whether or not animals should be returned to those who had left them behind while they fled to safety. Some felt that anyone who would do such a thing didn’t deserve to have their animals back; there were arguments. Everyone thinks, “I would NEVER leave my animals behind,” but suppose the rescue boat’s at your roof’s edge, where you’ve been waiting for three days and nights, there’s only so much room in the boat---and you can see your next-door neighbors and their four children, waiting on their roof for that boat, too. And we had to be reminded that people had often been told that they would be gone for only a couple of days and left their animals thinking they would be okay until they got back. There are no easy answers here. And that’s another ahimsa practice: loving one’s enemies. It was uncomfortable at times to be reminded that we were connected to those who left animals behind as much as with those who were saving them.

As you can probably tell, what happened in Tylertown was not that we all became saints. Not only did nothing miraculous happen to us, I would say that nothing happened to us at all. Instead, we simply moved through our days, cared for the animals and each other by being aware of why we were there, by deciding and choosing, and we learned where to go next in this unfamiliar territory precisely because it was unfamiliar: we were stepping outside the circle of our usual thinking and experiences. There were people of all ages, and whatever your abilities were, there was a niche for you. There weren’t any children when I was there--- the youngest person was maybe 18. There was a retired couple who guarded the front gate and checked everyone in and out. There was a woman who looked to be in her 80s who pretty much stayed in one spot, under a canopy out of the sun, but when you were looking for some specific item that had been donated, like waterless cat shampoo, and needed it fast, she knew right where it was.

It feels inevitable that we evolve in the process of seeing other people evolving: There was a lawyer, who was obviously used to being in charge and, as he put it, “yelling at people---I don’t get paid to be nice!” He spent his first evening at St. Francis Sanctuary trying to redesign the entire Best Friends animal identification system, despite gentle opposition from the staffers who had lost several nights of sleep to create it. The next day, someone suggested his size and strength would be useful down in New Orleans with the extraction teams, enduring 20-hour days catching terrified and hurt animals in surreal conditions---there was, for example, four inches of oil on the ground in one parish---and this was a deserted, flooded city, its waters a toxic sludge of chemicals from people’s basements and garages. He’d never done anything like this before, he said, but he went, and by the fourth night, he had dropped his façade and was saying, “I know I’m a jerk. I’m turning into my father. I can see it happening. But I only had to apologize for being a jerk three times today, and that was an improvement.” The next morning, I saw him tenderly hold and kiss a frightened white cat, who snuggled against his chest and closed her eyes as he stroked her---and I realized that I had not seen beyond his bluster to the evolving human underneath.

I thought I knew what to do when it came to cuddling cats (how hard is that, right?), but the animals taught me something new every day. There were LOTS of , cats, and they were in big cages stacked on top of each other in the cat building. We were always busy, always trying to find time to pay attention to ALL of them. But there was this quiet black cat who lay in the back corner of his cage at the bottom of the stack; with the cute kittens and very vocal cats demanding attention, he was almost forgotten. When I realized he was being ignored, I opened his cage door, not sure if he would respond with aggression or not---trauma can make even friendly cats hostile---but his eyes just lit up, right away, he began meowing and purring, and came right to me. TLC, one of the vets told me, was as important a component to their survival as veterinary care. This is no place for the animals to stay for too long; we had some “owner hold” cats who grew a little aggressive, starting to bite and scratch after being held for only a minute or so. (Owner-hold meant that their people had been located, and wanted them back, but were living in a shelter and unable to take them.) These two, Tender and Mikey were really ready to go HOME, and we all felt for them so. This is what animals can teach us: empathy, the opportunity to revere the sacredness of all life. And, as I said, all the cats made it, of course, as they had been injured too badly or their exposure to toxins was too great for their bodies to stand. So we learned to let go, a primary spiritual practice in all religions, by loving creatures with such short life spans.

After I got back, Linda, one of the volunteers who helped set up the shelter in the very earliest days of the rescue work, and came back again to help the week I was there, sent me an amazing story about a women’s prison in Virginia, which had taken in two dozen cats displaced by Katrina:

"Four Pocahontas Correctional Unit inmates have been caring for the cats since they made the cramped 20-hour truck ride last month from an overwhelmed Mississippi shelter. The women see it as a chance to help not only the abandoned pets, but also the hurricane relief effort, and even themselves. 'They've had a long journey,'said inmate Wendy Brickey, 45, her eyes brimming with tears. 'I get the chance to make it okay. It makes us feel like we can be a part of something - to be a part of the storm - to help out. We are so secluded from the world and there's somebody waiting on their pets. And while I might never meet them, I took care of them while they're getting their life together.' She immediately connected with Scarlett, a kitten so traumatized she wouldn't let anyone touch her. After months of love and patience, Scarlett began trusting Brickey, and now the two often cuddle up together. 'When I look at her, I see that after all this time, I'm not so wild anymore - and she's not so wild anymore.' (Associated Press, copyrighted)

As I said earlier, I think we’re afraid to enter into this kind of work because we’re afraid we’re going to be overwhelmed by suffering. We don’t volunteer at the local shelter, look at that animal rights display on the street corner, or make it a point to know what really goes on in a slaughterhouse, because, as Randour says: “…acknowledging such suffering, we fear, would have fundamental implications for how we lead our lives. But the price we pay for this self-protection is the restriction of our spiritual growth. To absorb the extent and depravity of animal suffering can raise us to a new spiritual level. This is the price of the ticket for animal grace. OUR expanding awareness may lead us to feel that we are experiencing disorganization of the self, a significant price…but what feels like a disintegration of the self in these periods of intense transformation is not the SELF breaking down but its DEFENSES. The breakdown of these defenses needs to be welcomed rather than feared, for they have dimmed our awareness and stunted our compassion. Their dissolution can free us spiritually…the structure of the old defensive self must die so that a new, larger, and more encompassing structure can be born.”

Maybe you want to go down South and help. The common assumption is that any animal who hasn’t been rescued by now must have died. But the truth is that the emergency is far from over: Animal Rescue New Orleans, aka ARNO, is still finding animals ALIVE INSIDE OF BUILDINGS. For those they haven’t been able to catch, they’re putting out food and water. They’re providing medical care, including spaying and neutering, which is the most crucial element in this equation. The Humane Society of the United States estimates there may have been as many as 50,000 animals left behind in New Orleans alone. And all the animals who survived the storm and weren’t spayed or neutered---and only around 2% of those who were rescued had been fixed---all of those animals are now breeding. 50,000 starving animals having babies, and time is running out. Animal Rescue New Orleans’ website is the place to donate, volunteer, and get updated: http://www.animalrescueneworleans.com. And check out the documentary that opens in a few weeks, “Dark Water Rising: The Truth About Hurricane Katrina Animal Rescues” its website is: http://www.darkwaterrising.com.

And sending money is important, definitely, but it isn’t always something that feels like a “complete” action---we all want to “do more,” and there’s a good reason for that: writing a check isn’t enough. To truly find your way to animal grace, to any kind of place of peace within, it’s necessary to refuse to be a passive spectator, and instead, become an active participant; the more you do, the better you will feel---as long as you know your limits. And you don’t even have to adopt or foster an animal---although that would be wonderful. At least 8,000 animals were rescued in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, and most are still in need of fostering or adopting. The tragedy of animal overpopulation is a preventable one, and it has been created a lack of mandatory spay/neuter laws, and control by death is the way we essentially allow Katrina to happen on a daily basis all over the United States---with an estimated 4-5 million cats and dogs being put to death in shelters every year. Another way to look at it is that by adopting an animal, any animal, from a rescue group, you will be freeing up space in those shelters for hurricane animals.

And what else can you do? You can make choices, every day, that will have a positive impact on the lives of animals---actually, you DO make choices every day, because your life intersects with so many animals, ones you don’t even see. Every day, we make choices: through the foods we eat, the personal care and household cleaning products we choose to buy, the clothes we choose to wear. Someone once told me that the only thing you can do wrong when it comes to helping animals is to do nothing at all. There’s a whole, undiscovered world of animal wisdom out there: we now know that animals have the capacity to create art and music, to use language, to grieve---you may have heard of Koko, the gorilla who uses sign language, and how she grieved when her kitten (whom she had named AllBall) was killed accidentally. We can choose to respect that world which is so connected to ours, so magical and important in the fabric of life here on Earth. When we do this, we grow spiritually and the animals benefit, too.

I don’t want to violate non-violence, ahimsa, or the Third Precept of the Order of Interbeing by trying to force you to adopt my views. I would like, however, to start a compassionate dialogue, within you and between you and everyone you meet, to become aware of our schizophrenic attitude towards animals that ranges between sentiment and violence, with little in between. None of us can attain perfection, but the idea of love can always keep us moving in the direction of compassion, love and awareness. As humans, we go to great lengths to separate and distinguish ourselves from other species, when we have so much to gain by instead moving closer to compassion by crossing boundaries, and finding kinship with all of life and creation. I never felt the truth of this as strongly as I have since my trip to Mississippi---and it’s changed my life forever. I was given a great gift, and it’s one we can all receive, every day.

Sunday, August 27, 2006

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)