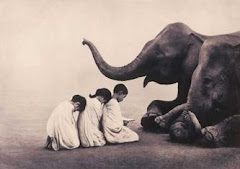

Will Tuttle's website has a daily inspiration for going vegan. The words and photos are always beautiful and positive. Thought I'd share today's "VegInspiration":

VegInspiration. Feeding the Shadow

Posted using ShareThis

(Posted by Marina)

Tuesday, January 19, 2010

Monday, January 11, 2010

“VEGANIC” GROWERS TAKE THE ANIMAL PRODUCTS OUT OF ORGANICS

Written by Lee Hall, and reprinted from "Action Line," the Friends of Animals' magazine, 777 Post Road, Darien, Ct 06820.

Climate meltdown is the animal farm’s real nemesis. How do agribusiness CEOs react? Some promise to reduce emissions by using new kinds of animal feeds. Others boast of plans to convert methane into electricity. If it’s a small company, perhaps the owners are describing the animals the buy, breed and kill as part of a natural ecology.

Animal activists have joined in, trying to improve husbandry practices or promote supposedly sustainable animal farms. “Incremental steps!” they say. But likely in the wrong direction.

In 1944, when just over two billion people occupied the planet and before the era of mass-scale industrial farming, Donald Watson and a few like-minded “non-dairy vegetarians” developed the vegan platform: Truly idyllic and sustainable animal farms didn’t exist in the early 1900s, and never will. Watson was a vegan-organic gardener -- steering clear of animal manure, bone meal, feathers or blood, instead using compost for fertility. We haven’t all reached this level of dedication in our own lives, and yet this would seem the best example of a model to set forth, so people know what to strive for. And today, there is an international network of vegan-organic farms. So why aren’t more animal and environmental advocates following -- or at least lending their support to -- their refreshing example?

In the 1970s, Peter Singer’s "Animal Liberation" (followed by "Animal Factories," authored with Jim Mason in 1980, and most recently followed by Singer’s and Mason’s "The Way We Eat") described large animal processing plants as horrifying places; but Singer has steadfastly maintained that breeding and killing can co-exist with the idea of treating animals fairly. In other words, Singer appears to believe that the animal factory, not animal farming per se, constitutes the ethical problem.

For humane reasons and also due to the “environmental costs of intensive animal production” Singer says “we need to cut down drastically on the animal products we consume.”[1]

But does that mean a vegan world? That’s one solution, but not necessarily the only one. If it is the infliction of suffering that we are concerned about, rather than killing, then I can imagine a world in which people mostly eat plant foods, but occasionally treat themselves to the luxury of free-range eggs, or possibly even meat from animals who live good lives under conditions natural for their species, and then are humanely killed on the farm.[2]

Farmers, restaurants and grocery chains have seized the opportunity. Whole Foods Market claims “to assist and inspire ranchers and meat producers around the world to achieve a higher standard of animal welfare excellence while maintaining economic viability.” Singer, together with an alarming number of animal-protection groups, endorsed Whole Foods’ Animal Compassion Foundation, which turned out to be quite lucrative for this internationally expanding corporation.

Celebrity restaurateur Wolfgang Puck was bathed in accolades by two wealthy animal-protection societies for buying only “sustainable seafood,” for indicating “interest” in processing plants that use a gas slaughter method, and for only serving chicken and turkey flesh from farms that comply with “progressive animal welfare standards.”[3] Red flag! Advocacy should never be about making exploitation appear to work decently.

It gets weirder still. In early 2009, Worldwatch Institute, a Washington, DC think tank known for its reports connecting animal agribusiness with climate change, announced a partnership with the Stonyfield Dairy company. The group’s communications director[4] told me, “ Stonyfield buys dairy from conscientious farmers and is constantly pushing those farmers to improve.” The advertising draw? This dairy producer has animal welfare in mind. The reality? Stonyfield uses animals for profit. The planet gets used up in the process. Dairy cows, who live longer than beef cattle and are overfed to stay as productive as possible, are associated with high methane emissions and feed demand.

Greenwashing is an international phenomenon. A few months ago, a British television station the documentary Pig Business, made by Tracy Worcester, who has worked on behalf of Friends of the Earth. Brimming with disturbing images (some of which were excised for the television audience), the film decries pig crates, rough handling, and cheap meat. Worcester points out that foreign pigflesh -- from the US-based multinational Smithfield, for example -- would fail British expectations of handling and housing standards. The film’s promoters laud small farms and local butchers.

“ I think we all fundamentally like pigs, don't we?" Worcester asks. B ut Worcester will eat bacon, the Telegraph newspaper assures its readers -- as long as it’s from “really, really happy pigs.”[5]

Those pigs aren’t happy, dear readers; they’re dead. Meanwhile, the owners of the supposedly happy animals are pressing free-living beings out of former wildlands. Moreover, animal agribusiness is notorious for its heavy use of fuel to transport crops and animals.

To get around that, we’re told we can be “locavores” -- buying dairy, eggs, and animal flesh as well as vegetables from area farmers or hobby farms, or dining at restaurants with local sources. But even Forbes has run an opinion piece questioning these ideas, citing a study by Rich Pirog of the Leopold Center for Sustainable Agriculture that connects transport to just 11% of food's carbon footprint.[6] “No matter how you slice it,” the comment observes, “it takes more energy to bring meat, as opposed to plants, to the table. It takes 6 pounds of grain to make a pound of chicken and 10 to 16 pounds to make a pound of beef.”

The conclusion? “ If you want to make a statement, ride your bike to the farmer's market. If you want to reduce greenhouse gases, become a vegetarian.”

Vegan-organic (also known as “veganic”) growers believe we can live without animal farms -- even without the by-products of animal agribusiness. ( The fruits and vegetables we know as organic are usually grown on farms that raise animals or use animal manures and slaughter by-products to fertilize their soil.) Some think a world without animal agribusiness isn’t possible, and call veganic growers idealists. Who’s right?

To answer the question, we could start by asking if continued reliance on animal farms is really sustainable. Domesticated animals must eat, and feed crops are invasive -- planted where great prairies and dense rainforests once flourished. Animal husbandry also puts tremendous pressure on the world’s water. Veganic growers are genuine liberators, freeing the land from grazing and fodder production, taking no more water than necessary, avoiding pollution, and returning part of the harvest to other beings and to the land. They’re cultivating respect, shielding and celebrating the freedom that’s still possible for animals who live in local ecologies.

Of course, vegan-organic growers are idealists; they hope to show society how to live without relying on a system that treats animals as products. But they will in turn point out that organic growing can’t spread much further as it is now, because the manure it uses needs to come from somewhere, and grazing land is already pushing out the rainforests. Trying to change animal agribusiness in increments -- say, by switching to “cage-free” eggs or supporting free-range concepts -- means forgetting that Earth’s space is finite, and the spread of pasture-based farming uproots free-living beings.

Brian Graff of the North American Vegetarian Society says supporting veganics is “not about reaching some notion of perfection.” Graff explains: “Either buying or growing your own vegan organics is just another avenue open to us to minimize our exploitation of the earth and its creatures.”

So if you’re fortunate enough to have veganic farmers in your area, you’ll be doing something important by supporting them. If you already cultivate a garden, seriously consider avoiding the use of manure and other animal derived products. For more about both of these ideas, check out the work of the Veganic Agriculture Network at http://www.goveganic.net.

FOOTNOTES

1] Quoted in Rosamund Raha’s “Animal Liberation: An Interview with Professor Peter Singer” in "The Vegan" (quarterly magazine of the Vegan Society; Autumn 2006), at page 19.

2] Ibid.

3] Farm Sanctuary joined the Humane Society of the United States in urging advocates to thank Wolfgang Puck for issuing these claims.

4] E-mail from Darcey Rakestraw dated 6 Jan. 2009.

5] Louise Gray and Charlie Brooks, “Marchioness of Worcester: The Aristocrat Standing Up for Pigs” (27 Jun. 2009).

6] James E. McWilliams , in “ The Locavore Myth” in "Forbes" (issue dated 3 Aug. 2009), states: “A fourth of the energy required to produce food is expended in the consumer's kitchen. Still more energy is consumed per meal in a restaurant, since restaurants throw away most of their leftovers.”

To read this article online at the Friends of Animals website, go to http://www.friendsofanimals.org/actionline/winter-2009_10/movement-watch.php

Labels:

Friends of Animals,

veganic growing,

veganism

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)